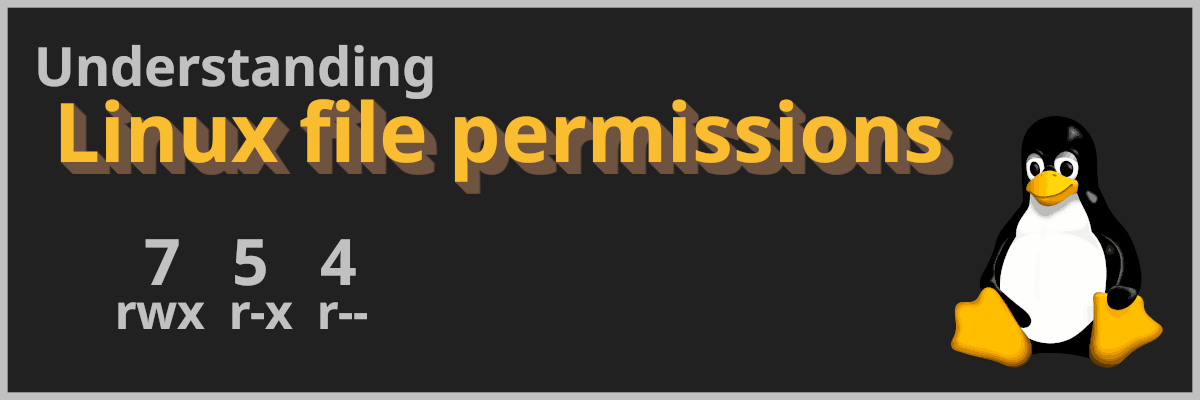

tl;dr: rwx = 0111 = 7. -rwxr-xr-x = 0111 0101 0101 = 755.

Ok, I want to make my file read/write/execute for me, and read/execute for

group and others, easy: chmod 755 my_file.txt. Of course I know this. Want

all permissions for everyone? 777. But, whenever I want anything else, I always

have to google it. Well… NO MORE!

Understand it to remember it

After years of always forgetting and not really knowing how the permission for files are in unix like systems, I finally, when looking it up, found a way to remember it. And I found the way to remember it so cool that I want to share it with you! (Also I wanna make sure I remember it, so writing a short post is the perfect way).

First of all. What are the permissions, and what do they look like? Here is an example with a few some files:

~/test-directory $ ls -la

drwxr-xr-x. 1 lars 88 Nov 17 13:51 ./

drwxr-xr-x. 1 lars 42 Nov 17 13:50 ../

-rwx------. 1 lars 0 Nov 17 13:50 my-script.sh*

----rwx---. 1 lars 0 Nov 17 13:51 our-script.sh*

-------rwx. 1 lars 0 Nov 17 13:51 everyones-script.sh*

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 lars 69 Nov 17 13:52 link-to-script.sh -> /home/lars/tmp/script-in-different-directory.sh

-

d: directory -

-: file -

l: link -

r: read -

w: write -

x: execute

From the left: First is the type of file, then it is the permissions for the user that owns the file, which we can see is lars, then it is the group, then everyone else.

After creating the files I ran chmod on all of them. Editing the permissions. I also created a symlink.

chmod 700 my-script.sh

chmod 070 our-script.sh

chmod 007 everyones-script.sh

ln -s /home/lars/tmp/script-in-different-directory.sh /home/lars/tmp/test-directory/link-to-script.sh

Bonus fun fact about symbolic links

Notice how the symlink seems to have rwx for all, but this is actually not the

case. The permissions are set by the target file, which in this case has 755

(just trust me). For some reason Linux creates symlinks with 777 by default,

but these permissions are not actually correct.

Binary

Before we get to the really good stuff, I need to give you a quick reminder of how binary numbers work. Feel free to skip this part if you’re already comfortable with binary.

So, as we know, with “normal” counting we go from 0-9, then add a new 1 on the 10

place ..8, 9, 10, 11... In binary we only count to two: 0, 1, 10, 11.

The value how ever isn’t “zero, one, ten, eleven..”, it is still “zero, one,

two, three”. This means that each number place is not “1, ten, hundred,

thousand”, but “1, 2, 4, 8”. See the pattern? It doubles. Decimal counting goes

to 10, each place is times by ten. Binary goes to two, each place is timed by

2.

If we use binary counting when counting on our fingers we will get to 1023. Using each finger as a bit. I wonder if this would have given me a better edge if I learned this first when learning counting and math in elementary school.

What number is what permission?

Back to permissions. So how do we remember what permission is what number? We

know 700 is rwx------, so 7 = rwx and 0 = -. But what about 3,

or 2 or 6? They trick is thinking of a byte, or a nibble actually. That is half

a byte, four bits. Actually, we only need three bits: 000. Think of each

of these bits as switches. From the left: The first switch sets the read

permission. The second sets write, and the last one (or the first (from the

right) to be more correct) sets execute.

So if we want to give the user read and write permissions, we need to set the

“read bit” and the “write bit” rw-. That would look like this 110 in

binary, which is 6 as a decimal number. And if the group should only read

that is r--, which is 100 = 4. And we give others read and execute: r-x

= 101 = 5. The command to set this would then be chmod 645 filename.

Special permissions

But wait, there is more. There are actually even more permissions to set. Three

special permissions. And we can think of them in the same way as we did with

rwx, as set by three bit switches 000.

The first bit from the left sets s(pecial) user. Or SUID. 100 = 4 So we

can set it with chmod 4xxx filename (or with chmod u+s filename). This

will make the file always execute as the user that owns the file. This is

useful if we for example need to run a program that needs root privileges, but

we want to be able to run it as any user. Like mount.

ls -ld /usr/bin/mount

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 48896 Mar 17 2025 /usr/bin/mount

We can see there is an s at the owner where the x should be.

As a user you can execute the binary. But it needs to run as root since it

needs to access kernel functions which are restricted to root.

Then we have the second bit. That sets GUID. G as in Group. 010 = 2 So

we can set it with chmod 2xxx directory_name (or with chmod g+s directory_name). As with SUID, files with the GUID bit set will run as the

group. If we set this on a directory, all files created in this directory will

be owned by the same group as the directory. This could be handy when

collaborating with multiple users so everyone in the group can access all the

files.

The last bit is called sticky bit. 001 = 1 So we can set it with

chmod 1xxx directory_name (or with chmod o+t directory_name). This

makes all the files in a directory “stick”. They can only be removed by the

owner or root. We can recognize it by the t at the end.

~ $ ls -ld /tmp

drwxrwxrwt. 37 root 900 Nov 20 21:07 /tmp/

I wouldn’t recommend using the special permissions on any files or directories unless you really know why and what you are doing, since they can quickly become a major security problem. As if you run anything as root you are able to cause all the damage you would like or not like.

Conclusion

Now we should for ever remember how to set all the file permissions we want.

Hope you found this as interesting as I did!